On Sunday June 2, working with students and volunteers in their community garden at Schumacher College, Dartington, I combined planting potatoes for research into potato yields with the residuals practice of dance making and mark-making. I call this an ‘integrated research practice’ as the residuals practice is a research too.

Science practice

Besides the residuals practice which I’ve previously described in this journal of using charcoal drawing in a movement practice, I’ve also been researching charcoal used as a soil enhancer for increasing the yield of potatoes. Used in this way, charcoal is known as bio-char but it’s exactly the same material. Indeed the charcoal used to-date in the residuals project, is charcoal granules which are sold as bio-char. ie an agricultural product was re-purposed as an artists material.

There are ten trials of potatoes on six different sites – all planted in the 2024 growing season. The crop trials are co-created. That is, I am providing an experimental design and bio-char (charcoal) to gardeners for them to study crops yields in their potatoes. We are co-reaserching biochar in a ‘citizen science’ project. To date, research like this has been conducted in agricultural studies at research centres, universities, etc. But my research – with the other gardeners – is ‘real world’ research.

The trials are very simple: an equal number of potatoes are planted with biochar, and without biochar (a control) at the same time. A comparison is made of the weight of potatoes harvested for those grown with bio-char and those without. The gardeners may use whatever cultivation regime they wish: with or without fertiliser or compost for example, as long as the same regime is applied to both the cultivation of bio-char and control potatoes.

Architecture and movement practice

Prior to the performance of Residuals #4, I considered how the crop trial at Schumacher would be laid-out: its architecture. To date, the potatoes have been grown in trials where the bio-char and control are planted side by side and in a line – as far as I know! But why not arrange this differently? Indeed the project is about accepting differences in cultivation while also studying the effect of biochar. It’s research for a population level study.

Hence in the Schumacher community garden, the design was that the biochar potatoes would be in the centre and then the non-biochar control would be arranged in a ring around it so that it looked like a target or bullseye design in layout.

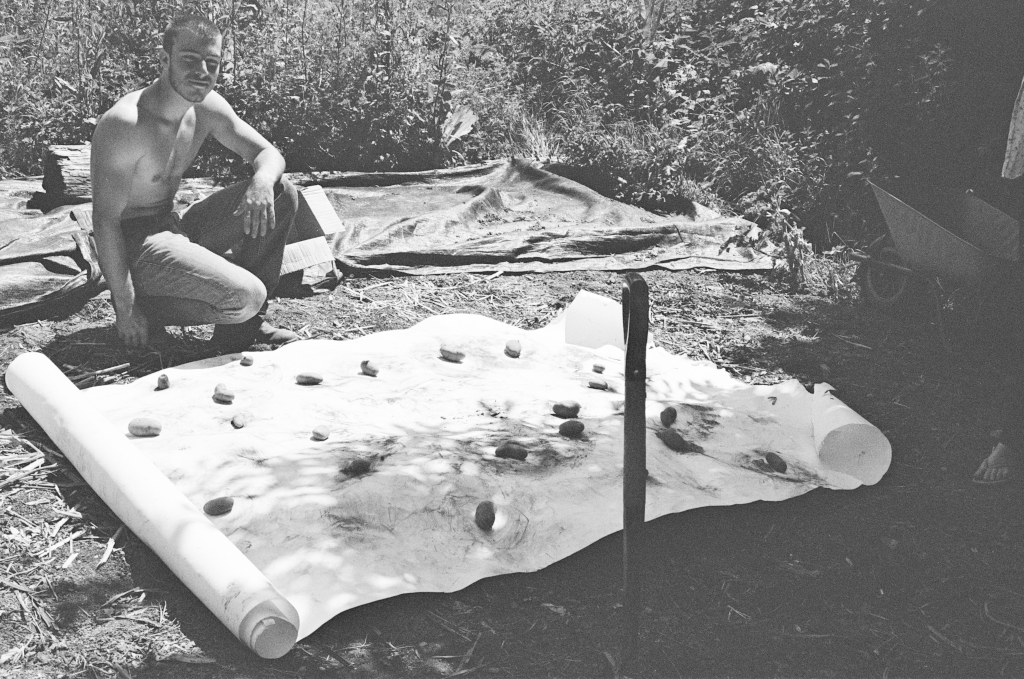

The four gardening performers: me, Jacopo, Therese and Debra created this design through our movement practice.

The Gardening Practice

There are some simple facts about potato planting. The seed potatoes are above the earth and need to be planted into the earth. The bio-char similarly. For the mark-making then charcoal would need to be pressed and moved – impressed – onto the surface of the paper.

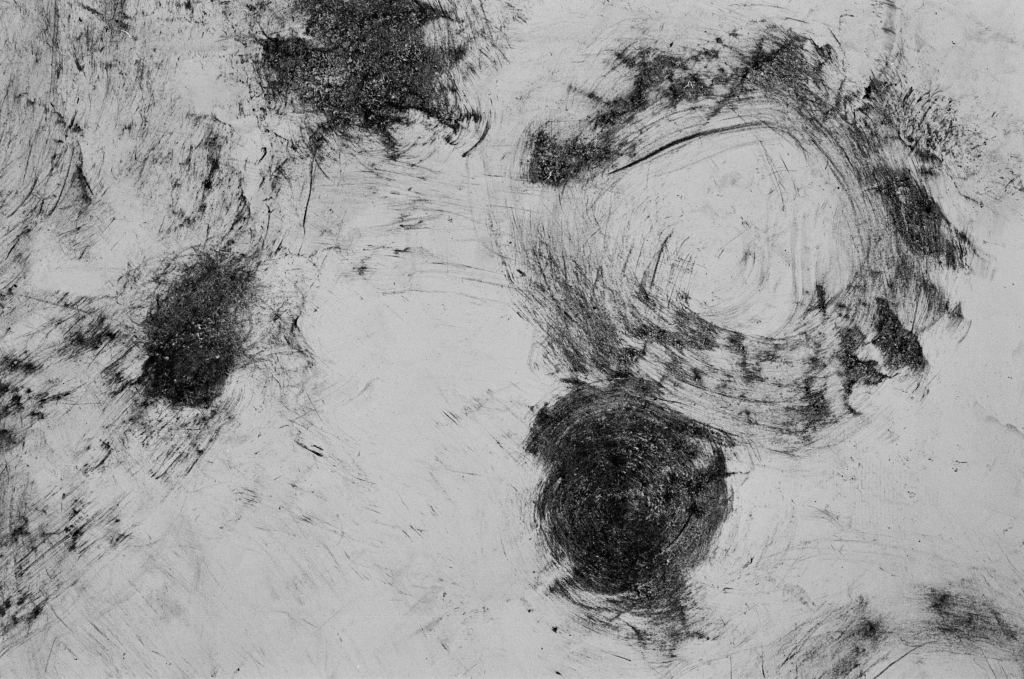

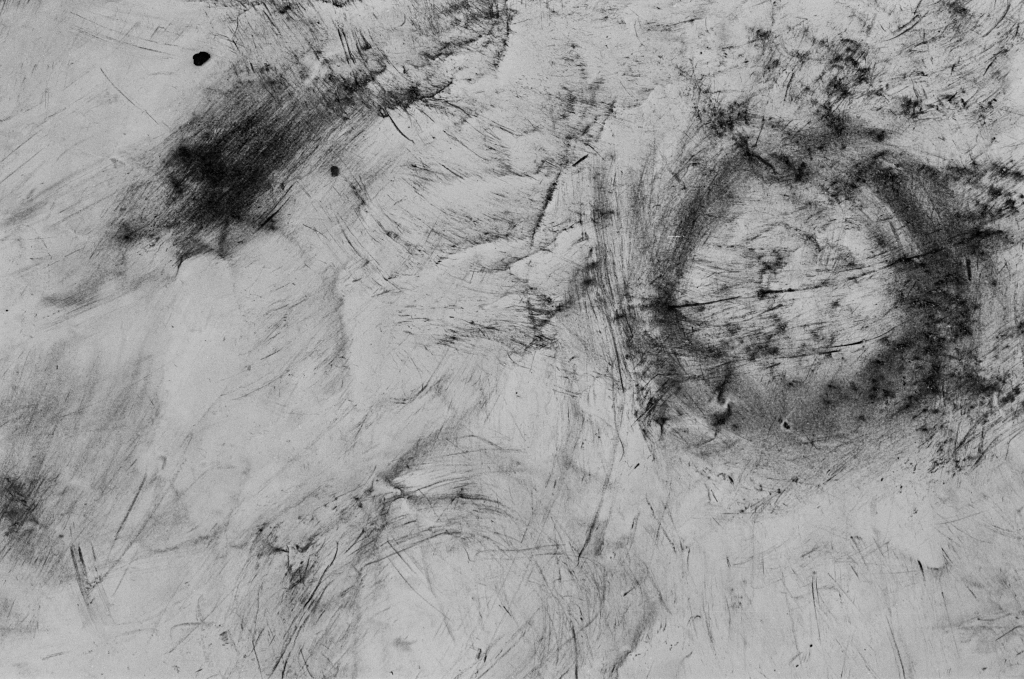

I conceived a score whereby the paper would be laid upon the soil where the potatoes where to be planted, and the potatoes and bio-char would interact so as to mark the paper. ie the potatoes would be used as a template to make a pattern in an improvised way.

I also devised a simple score for the pattern. Some of the potatoes were a variety with a red skin and some of them had a white skin. Where the potatoes were white then the potato would be placed on the paper and the charcoal drawn around it – creating a circular outline. But where there was a red potato then the charcoal would be pressed and drawn onto the paper and then the red potato placed upon it. We could say that the potato drawing thus retained the potato colour: white is a white circle; red is a dark circle.

What happened?

There’s a lot of detail in the description below. To summarise: the potatoes were planted as required for the crop trial; the gardening performers created a movement practice for gardening, and we made a charcoal drawing.

Firstly, we placed the paper on the soil where the potato trial was to be planted. The contents of a bag of bio-char were emptied into a pile in the centre of the paper. The potatoes of both colours were placed on the pile. We looked upon the bio-char and it was slightly wet. It cracked in the sunlight as if singing to us.

Each person had one gardening glove – there were two pairs of gloves which gives four gloves – one for each of us!

There were some parts of the movement score (composition) which I’d not devised at all but were simply improvised. For example, the potatoes – which were initially emptied from their bags onto the charcoal pile needed to be counted out, and there needed to be an equal number of red and white potatoes in each set. One of these sets would have biochar and the other set none as it was the ‘control’. Somehow, I missed this detail in the design of the score!

Also, there was not an even number of potatoes for the trial so we cut one potato in half to given an even number for the biochar potatoes and the control ones. This potato had sprouted shoots on each half of the potato and hence it would grow as two potato plants when each half was planted separately.

The set of potatoes left on the pile of biochar were now all ones which would be planted with the biochar. We each took a potato and used it as a drawing template for the charcoal as I described above. Each of us gardening performers decided where the potato drawing was located on the paper. Later I realised that we had created a plan or map of where the biochar potatoes would be planted – roughly.

We’d distributed the bio-char potatoes about the paper – reaching with our hands to move them and the accompanying charcoal from the central pile, and drawing them. Our reaching for the potatoes draw them from the pile, and then we draw the potatoes with the charcoal. I love how ‘drawing’ is both a verb and a noun: sliding between being and doing; process and structure; practice and outcome.

With the potatoes set in their place on the paper, we turned our attention to the pile of biochar. The four of us then stood over the pile of bio-char and held a gloved and outstretched hand against it, impressing it upon the paper. We walked around the pile, rotating the bio-char as if a wheel and creating a circular movement, drawing it upon the paper and mark-making. Hence there was now a large circular shape and the potato shapes in the drawn image.

After creating a planting drawing, we needed to fetch compost in wheel barrows to put on the surface of the earth. Thus the paper and potatoes were put aside while the laying of compost was completed. In the photos then the darker soil is actually compost. You’ll also notice how the final design of the ring and bullseye is instantiated: the darker compost creates this marking on the ground. The biochar was then lightly dug into the central circle.

Once that was completed then the paper and potatoes were returned to cover the central circle of biochar.

Then there was the task of moving the potatoes from being on the paper, to being on the ground prior to planting. We considered cutting the paper surface with a knife, to push the potatoes through and onto the earth but decided to simply reach under the paper with the potato and deposit it there with our hand. No paper was cut!

Finally, we could plant the potatoes in the ground and in the areas for the comparison of those with biochar in the centre, and those in the outer ring without it.

The planting practice was completed.

What next?

The potato plants will grow and show the geometric arrangement which we created in our planting.

There is a practice to consider for digging the potatoes out when ready for harvest in September, and I hope, a harvest supper where we cook and eat some of them. Oh yes, and weigh the potatoes in the trial to compare the efficaciousness of bio-char and non-biochar cultivation.

There should be plenty of potatoes for the kitchen store at Schumacher college, for future meals, and the students and visitors to them. Fingers crossed!